Contratapa (edición de 2007):

Mito e historia. Leyenda y humor negro. Esta provocativa y excelente novela de Luisa Valenzuela reconstruye -con la libertad de la literatura- la vida de uno de las figuras más tenebrosas de la política argentina: el secretario personal de Perón y ministro de Bienestar Social. José López Rega, alias El Brujo, el oscuro personaje creador de la Triple A. de cuyas múltiples y misteriosas aristas sólo la incisiva escritura de Valenzuela puede dar cuenta.

Contratapa (edición de 1983):

Un Brujo que gobierna la tierra de nadie fabula desde los hormigueros secretos del poder el nacimiento de su imperio: el fétido Reino de la Laguna Negra. Su trono, a la vez escondite y centro de operaciones, es la réplica de una pirámide azteca. Desde ese templo de sacrificios, ríos de sangre correrán según la vieja profecía anunciada mil años atrás, cuando el Brujo llegó a ser el super ministro de un país real: la Argentina.

En una novela que se vale del mito y la historia, la leyenda y el humor negro, la autora -de quien Carlos Fuentes ha dicho que “es la heredera de la literatura latinoamericana”- reconstruye con total libertad la vida de un tenebroso personaje que manejó a su antojo los hilos de la política argentina: el todopoderoso José López Rega, secretario personal del general Juan Domingo Perón durante su última presidencia (1973-75), y apodado “El Brujo” por sus dotes de “hechicero emisario de los dioses”.

En la convulsa Argentina de los años 70, se cerraron las represas del pensamiento y se abrieron las del terror, cuando al frente de su engendro, el grupo paramilitar Triple A, López Rega inició la tarea -que los militares habrían de continuar con saña- de “desaparecer” a cerca de 30 mil personas.

El Brujo de la novela se siente invencible mientras alimenta su sueño de megapoder al amparo de un talismán único: el dedo amputado al bello e imperecedero cadáver de La Santa Muerta, Evita Perón. Autora, editores, lectores, todos estamos haciendo lo imposible para aniquilarlo. Necesitamos su ayuda.

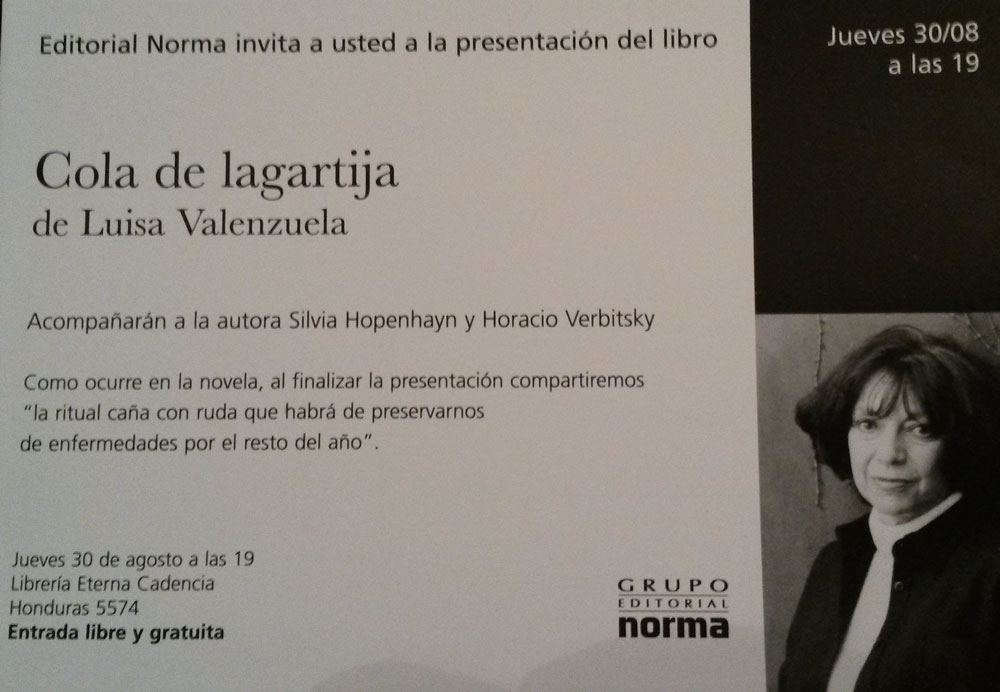

Presentaciones destacadas:

“Leerla es tocar de lleno en nuestra realidad, allí donde el plural sobrepasa las limitaciones del pasado; leerla es participar en una búsqueda de identidad latinoamericana que contiene por adelantado su enriquecimiento. Los libros de Luisa Valenzuela son nuestro presente pero contienen también mucho de nuestro futuro; hay un verdadero sol, verdadero amor, verdadera libertad en cada una de sus páginas”. (Julio Cortázar)

“Luisa Valenzuela s la heredera de la literatura latinoamericana. Usa una corona opulenta y barroca pero tiene los pies desnudos”. (Carlos Fuentes)

“Luisa Valenzuela ha escrito una novela maravillosamente libre, plena de ingenio, sobre la sensualidad y el poder, la historia y la muerte, el yo y la literatura. Solo alguien de América Latina pudo haber escrito Cola de Lagartija, pero no hay nada parecido en la literatura latinoamericana contemporánea”. (Susan Sontag)

Paranoia del poder demoníaco en una gran novela

por Juan Jacobo Bajarlía, en Nueva Presencia (Buenos Aires, diciembre de 1983).

El poder es una cola de lagartija. Un látigo trenzado de violencia en cuyo tejido gimen las voces anónimas, la destrucción del ser y la misma locura. Detentar esa cola es manejar las fuerzas oscuras de la magia, la fuerza de un poder enigmático que se alimenta de supersticiones, de falsos mitos que aún recorren la sangre. Tales son los significados que se codifican en Cola de lagartija, novela de Luisa Valenzuela, publicada previamente en Chicago como The Lizard´s Tail (1983) (La cola de la lagartija).

Código de locura y de muerte

El Brujo, su protagonista, transfiguración de José López Rega, usará estos poderes, estas tinieblas que cayeron sobre los argentinos en el tiempo ominoso de su reciente historia. El Brujo manipulará la violencia, la debilidad de los dictadores. El látigo será su cetro del mal, esas fuerzas oscuras, prelógicas que lo investirán de un poder demoníaco. Pero el ejercicio de la violencia incluye el del sexo. El Brujo Hormiga Roja, Señor del Tacurú y su Hermana Estrella (nombre epónimo del primer título, luego desechado) tiene tres testículos: dos que pudieron ser y un tercero supernumerario. De este tercer testículo, que será besado santamente y constituirá la trinidad demoníaca, nacerá, en extraña androginia, la Estrella impúdica (su otro sexo), que se abatirá sobre el crimen. Sería el símbolo aglutinador de la AAA, de las aes enrojecidas. La maldición, los muertos, los desaparecidos. Las lloriqueantes sin rostros de las santas locas buscarán entre otros rostros que perdieron el rostro.

Parábola del poder demoníaco y la violencia. Parábola e imagen en cuyos ojos, perdida la luz, brillará el infierno de los que se fueron para vivir en el recuerdo de la ignominia. Ni Calígula, incestuoso y cohabitando con su caballo, ni Claudio César, liberando el hedor de sus nalgas. Ni aun el mismo Nerón, haciendo asesinar a su madre, (“¡Hiere en el vientre, centurión!”) fueron tan abyectos como el Brujo. Luisa Valenzuela nos eriza la piel. Nos la pone de gallina. Congrega a Sade con Masoch. La crápula fetichista con Retif de la Bretonne. El humor negro con la semiosis del poder. El poder con el odio y el sexo.

Introducida en este mundo violento, la prosa de Cola de lagartija, a pesar de los inesperados laberintos, ha estremecido a su misma autora. Escrita en Nueva York, en la perspectiva lejana de ver correr la destrución como desde una platea alucinada, Luisa Valenzuela ha utilizado sus entrañas. Todo el cuerpo. Los cinco sentidos físicos, más el sexto de la percepción extrasensorial. La ESP de la potencialidad parapsicológica, desde cuya altura concreta la precognición de un diario que antes no existía, La Voz.

Y por encima de todo, las voces. La voz humedecida, llena de miedo. Y las otras voces que se oyen. Las voces de la sombra, únicos seres vivientes: la del Narrador, la del Hechicero, la del Garza, la de la Mujer Muerta, la de los Generales y la de la propia Valenzuela. Las voces del odio o la esperanza. Las únicas voces que decían del mundo lo que las tinieblas buscaban.

En el capítulo I la autora nos presentará sus símbolos:

“La tierra crujiente reseca por el sol agrietándose en sonrisas para mí, abriéndose en carcajadas hasta llegar a los tacurús, esos castillos. Y las hormigas tan diminutas, rojas, ¿por qué tenían castillos y yo no? A mi hermana aún no la sabia pero creo que fue mi hermana, que habría de llamarse Estrella, la que me dio la idea.

El escozor lo sentí precisamente allí donde ella mora. entre mis piernas- y atendiendo a ese escozor inauguré la costumbre de instalarme en la cumbre de los castillos. No el castillo más alto aquella vez, todavía no alcanzaba, pero elegí uno como hecho a mi medida y me senté sobre el castillo y desmoroné el castillo. En realidad un hormiguero pero fue mi primer castillo y las hormigas me reconocieron como era lógico suponer y me cubrieron del rojo suntuoso de ellas mismas y resplandecí y vibré bajo el sol de la siesta. (..)

Manuel tiene tres pelotas, Manuel tiene tres pelotas, chilló en cierta oportunidad el opa Eulogio y fue lo único que chilló en su vida. Enseguida volvió a perder el habla y recuperó su mirada perdida de tarado. Como en aquel entonces yo todavía no me llamaba Manuel no me importó mucho. Mas bien lo viví como un elogio. Lo que ahora denomino el elogio de Eulogio. El homenaje a Estrella hecho por un opa mudo que sólo habló para señalarla. Mi primer milagro.”

Ahora el general y la hermana que le crece en el testículo supernumerario:

“Se lo conté muchas veces al Generalísimo, variando eso sí algo el texto. Los milagros pueden ser elásticos y el Generalís comprendía esas cosas aunque para otras hay que reconocer que era un poco obtuso (por eso fallé en mi ultimo intento con él y no pude devolverlo a la vida: por su pertinaz obcecación) (Toda la luz que quise brindarle y él sólo la recibió en vagos resplandores. . .) Pero el Generalísimo es secundario, ya hablaré de él cuando le llegue el turno. Por ahora y siempre el turno es mío, le cederé una pizquita cuando a mí se me antoje e o quizá cuando Estrella lo reclame con fuerza. Ella lo amó, creo, aunque siempre tuvo la delicadeza de tratar de ocultarlo. (…)

Estrella. La que fue descubierta por las hormigas coloradas. Fue la única que conoció las mazmorras de hormigas, sus túneles secretos donde maman la vida. Yo me senté sobre el castillo de hormigas y destruí el castillo. Ella quedó colgando dentro de las entrañas del castillo yo me había quitado toda la ropa en esa siesta para penetrar el mundo de castillos, sin saberlo ya sabía que el verdadero ropaje sería el manto pulsátil. Gracias a lo cual Estrella, cuya existencia yo aún ignoraba, penetró los derrumbados dominios de la hormiga y supo su secreto y charló con la reina. Simples circunstancias que la llevaron a ser la reina y a mí que la involucró su dios omnipotente.”

Después las mazmorras:

“Para mi uso personal yo soy la droga, la droga soy yo y las hormigas libaron de mis poros, de mis más privados intersticios, razón por la cual siento que no les he robado nada al construir este mi castillo subterráneo con túneles y pasajes, puentes y pasarelas, mazmorras y cárceles y esos respiraderos como torrecillas, que vistas desde el aire parecen un campo de tacurús.”

Y luego la ubicuidad del Brujo, la noche infinita que se multiplica en una búsqueda cuyo lugar sólo conoce él mismo desde su fragmentación en las tinieblas:

“Los otros, los que se supone son mis enemigos, no pueden actuar sin mí y me consultan. Usando intermediarios, dando todo tipo de rodeos, pero igual me consultan y yo les sigo el juego: me hago el que no sé y me oculto de esa gente del gobierno, sólo permito que emisarios disfrazados me encuentren, me transformo y me entrego a las metamorfosis más complejas para impedir que me encuentren permitiendo siempre que me encuentren y alentando los resultados.

Me importa manejar los hilos aunque nunca aparezca mi nombre en los periódicos. He borrado mi nombre, sólo muy de vez en cuando alguien atina a llamarme don Manuel y yo no lo estimulo para nada, la opinión pública no me interesa en lo más mínimo y prefiero que crean lo que creen: que me he vuelto invisible, que me ha tragado la tierra. Oficialmente nadie puede encontrarme, ni los gendarmes, ni la policía de mi país, a pesar de que una vez fueron mis colegas y conocen mis mañas, ni Interpol ni la CIA ni el FBI ni la KGB ni ninguna de esas siglas que fueron especialmente creadas para no encontrarme. Soy invisible por dos razones a cual más meritoria:

Sé camuflarme bajo sus propias narices. Me he vuelto imprescindible para los que imparten las órdenes.”

En estos párrafos están el García Márquez de Cien años de soledad (1967) y el Asturias de El Señor Presidente (1946). Están en espíritu y efigie, como está la destrucción de “The Day after” (1983), el filme compulsivo del día después en que todos los cuerpos se hallarán en las tinieblas.

Parábola del poder que sólo engendra el miedo y la dictadura, el crimen anónimo y la ceguera, Cola de lagartija se yergue con un látigo (el látigo de su látigo) para testimoniar esa historia de sangre que asoló a la Argentina desde el asesinato de Aramburu hasta poco antes del advenimiento de Alfonsín.

El río de sangre

El libro se abre con la profecía de Don Orione: “Correrá un río de sangre y vendrán 20 años de paz”. Luisa Valenzuela da testimonio de esa sangre desbordante. De esa sangre llena de gemidos. De burbujas por donde salía el aliento de los que morían por una causa o por la inocencia.

Pero Luisa, al dar esta testificación, espera la paz, el don de la profecía. ¿Se resolverá o aun esa sangre seguirá corriendo?

El Chicago Tribune (del 30/X/1983), con un título fervoroso, “Una argentina exiliada da una estocada mordaz a su patria”, al comentar The Lizard´s Tail creía aun en el río de sangre. Transcribo parte de ese comentario.

“El Hechicero es andrógino, es un demonio perverso. Su dominio es la Laguna Negra, que él gobierna desde el Tacurú, una antilla gigante. Experto en torturas y represión, se embarca en una carrera mágica de agravios para extender su dominio. Al hipnotizar a su sicofante, el Garza, puede invocar el espíritu y la voz de la primera reverenciada esposa del Generalísimo, a la Mujer Muerta. Irradia esa voz para incitar a sus seguidores. Usa un dedo cortado de la mano de la Mujer Muerta (una referencia a circunstancias ocurridas en torno al cadáver de Eva Perón), para dejar huellas digitales de su segunda aparición (de la aparición de ella).

“Construye una pirámide azteca como símbolo de los poderes a que aspira, o sea ‘una metáfora convertida en realidad’, y arma una orgía de celebración. Esta orgía está parodiada por los habitantes de las localidades vecinas. Y cuando todos están presentes, las anexa a la Laguna Negra. Finalmente con los generales de la capital, el culto a la Mujer Muerta y un grupo de disidentes, Valenzuela también entre ellos, y todos furiosos por el calor de su cola, el Hechicero se transforma en una mujer, y da a luz un río de sangre.”

¿Se cumplirá entonces la segunda parte de la profecía? ¿Estamos ya en el alba de esa paz que durará veinte años? Si el río de sangre ha corrido entre oscuros vericuetos y túneles inacabables, ¿alboreará el nuevo día sobre esa porción del mundo que es la Argentina, y como tierra de los argentinos, una tierra del mundo? La pregunta está implícita en la novela de Luisa Valenzuela, aunque ésta sigue creyendo que las tiranías ya no vienen como antes, porque ahora tienen piezas de repuesto. Pero testimoniar sobre el horror ya es de por sí una perspectiva, la espera del alba. La autora, en esta gran novela, apunta hacia la destrucción del látigo trenzado. Y como Edgar Allan Poe, podrá decir “Never more”. Nunca más.

Into the heart of darkness

por Elizabeth Hanly, en In These Times (Jannuary 11, 1984).

A frolicking, wisecracking, fingerlicking witchdoctor is loose in Luisa Valenzuela´s most recent novel, The Lizard´s Tail. He calls himself Keeper of Pain, Keeper of Fear. Valenzuela´s coup here her triumph- is a creation of a language and a structure that allow the reader to poke around at her Sorcerer and eventually to stand close enough for him to sical the air one breaths.

The Lizard´s Tail is in part Valenzuela´s effort to understand how a decade of bloodletting came to pass in her native Argentina. Thinly veiled historical references constantly reach out to the reader. The whole Peronist gang is here: the Generalíssimo (Juan Perón), the Dead Woman (Eva Perón), her successor the Intruder (Isabel Perón) and later, after the 1976 coup that ousted Isabel Perón, the disembodied and nearly indistinguishable voices of all those generals with their talk of national reconstruction and getting away with murder, the Sorcerer strolls, lord of it all, underground amid his Indian maidens, his slaves, his honeypots and his instruments, at home in, quite literally, an anthill paradise Valenzuela´s Sorcerer is modeled after López Rega, Isabel Perón´s minister of wellbeing. An intimate of Isabelita´s López Rega published several volumes on sorcery and is also credited with creating and nurturing Argentina´s AAA an extreme rightwing, paramilitary terrorist organization with innumerable tentacles.

But to consider The Lizard´s Tail only as political parody is to head cocksure into a labyrinth. Valenzuela is interested in myth. She´s among those who equate mythmaking presupposes a deep dive into the unconscious. There´s a hole tradition, to which Erich Neumann´s Jungian classic, Art and the Creative Unconscious is central, which argues that the artist as hero is responsible not only for mirroring a culture but for healing it. Patterns, textures and figures brought up by the artist can gradually reshape the cultural cannon, making it more complete. This same tradition defines myth as the collective dream of a people. And, as in the dream where all the characters, the fragments, even the colors are reflections of oneself, so Valenzuela enters into the story.

There are a handful of voices in The Lizard´s Tail; most are developed with fist- person narrative. Valenzuela is there, disturbingly close to the Sorcerer as he ruminates about his natural right to cause pain. She´s there again, a play within a play, as the writer who wrestles with her fictionalized biography and then, after receiving an invitation from her character to his Bacchanalia, must wonder who is creating whom. And all this is happening, even as her own lover is being tracked in the brutal Argentine style of the mid´70s- by the AAA.

A certain cadence runs through The Lizard´s Tail. It´s always there; sometimes broad and leisurely, sometimes tightening to a climax. Riding this rhythm on almost every page are the words of an old Argentine prophecy “A river of blood will flow”- which goes on to promise 20 years of peace.

There is no peace here there´s barely a plot here- but there is a river of language as rich as blood. Nothing is static in The Lizard´s Tail. Valenzuela hinges her story on images and metaphors, mostly organic ones, multitudes of them- always moving, colliding, expanding, recreating each other like a kaleidoscope. Most every metaphor suggests another one. Images pierce through all the layers, stunning the reader with all their accumulated meaning.

But Valenzuela the poet is never far from Valenzuela the punster. There´s a logic in the language that prickles and teases and a rèlentless humor that keeps the reader offbalance.

The Sorcerer wants a child more accurately, the Sorcerer wants a son. He´s betting he can outsmart the earth and have one “without the help of any woman, without the support of hostile powers.” A great deal of the novel´s action revolves around his preparations to do just that. Early on one discovers that the Sorcerer has a third testicle that he regards with rapture as his sister and soulmate, his feminine aspect- Estrella, the Morning Star. Estrella will bear their child. Later, however, the Sorcerer has serious doubts about whether to allow this birth or whether “I myself shall retain I myself forever in my innards.”

Feminine values are spat upon here. Indeed, the Sorcerer plays regularly with chemicals, hoping to find a combination to speedily dissolve as many uteri as possible. No more corruption, he reasons. With Eros plucked out at the roots, what remains is bloodlust. Valenzuela speaking as herself in the novel, describes the effects of a meltdown of such feminine values. “I no longer feel time passing in me. I only know of separation, a great cultural broth of separation.”

There is no redemption in The Lizard´s Tail. It´s hardly conceivable in this world. What an adventure it would be to watch Valenzuela apply her wit and her tumbling words to that theme. As it stands, The Lizard´s Tail is finer than any net that tries to catch it. A brilliant dissection of fascism and paranoia, the novel is perhaps most truly a prayer for strength to face one´s demons, individually and collectively…Lest we forget.

Wise Blood – Argentine Alchemy

por Enrique Fernández, en Voice Literary Supplement (October, 1983)

Like all writers, Latin American novelists hold a continuous double dialogue: with their craft and with the world, that reality which literature usurps. Both dialogues can be bleak. The radical pessimism and nihilistic impulse Latin American have been imbibing from modernism since the turn of the century lead to hell, and hell, in Latin America, is a specific adress in your city; its devils are people who shop in your supermarket. Imagination, the dominant faculty in contemporary Latin fiction, seems to burn just as brightly in the Latin dungeon. With Latin American political life ablaze in the news and modern Latin fiction reaching a wider readership (the current “boom” revival), it´s not surprising that there´s a strong impulse to connect the two, to read fiction as the key to volatile, savage, threatening reality. Such readings, no matter how well intentioned, have traditionally encouraged North American naiveté (and noblesavage critical attitudes) about the Latin world.

Contemporary Latin fiction is characteristically dense, requiring an active, cultivated reader capable of locating the text within a vast interplay of international letters and critical thought, not one who will take literature literally. In the long run, however, the power of the text will prevail. North American readers will not pick up much valuable data from their readings of Fuentes and García Márquez, but they will, once the outragedatinjustice liberal response is left behind, begin to deal with Latin American culture and political life in its complexity. They will begin to understand the mind that forges the trope, the torture, and the radical revolt.

At first glance, Luisa Valenzuela´s new novel seems to encourage a literal, historicopolitical reading. The Lizard’s Tail is a roman à clef with the answer on the jacket: “It is based on a real story the career of López Rega, Isabel Perón´s Minister of Social WellBeing, who, for all intents and purposes, ruled Argentina literally through sorcery. The Lizard’s Tail follows this Argentine Rasputin as he plunges into the depths of pleasure and degradation that absolute power can avail. The Sorcerer is a Sadean libertine in the heart of darkness: where Western paranoia meets the jungle and mumbo jumbo will hoodoo you.

Bored with golden showers and virginwhipping, the Sorcerer turns more and more to the creation of his own Oz in the swamplands, ruling through cruelty and becoming what all tyrants eventually become a fairytale monster rattling around a haunted palace. There are many signposts in the text to remind us of the Peronian setting (at one point the Sorcerer, who never mentions names, almost gives the game away by uttering “E…!”). and Valenzuela places herself in the novel as writer of the text, its master, and narrator of the story, its witness. Like the Sorcerer, she is the author of perversions and horrors, for these are in her novel; writing is a guilty business to be atoned by political commitment, the path chosen by the authorinthetext, the narrator, who is part of an underground cadre.

Valenzuela is writing about a historical figure. Her author/narrator acknowledges this when she muses on the two Sorcerers, the one she has created in her fiction and the real one. In the end, she uses the text as incantation, the faculty of fiction to replace history tightens around the Sorcerer, and she feels the squeeze: there’s a writer out there after his ass. This may be Valenzuela´s finest literarypolitical lesson: slay the ogres in the text, surround them with their own heads staked on pages, juju them. In The Lizard´s Tail, the man of power is condemned to a monstrous femininity. Born with a third testicle he calls “my sister Estrella”, the Sorcerer can make it swell like a womb.

Dusan Makavejev once predicted that when women got control of film and the media we would see “a lot of blood, a lot of shit” (Makavejev, a Reichian, does not use “shit” pejoratively). This novel by the new (and rare) female star of the Latin American pleiad revels in primal ooze. In The Lizard´s Tail, the world feels like a pulsating, disemboweled body; for the Sorcerer, cruelty is just a way of going with the flow of blood, ants, water, mud. In this fluid state, metamorphosis is the order of the day. The Sorcerer´s lover/slave/disciple becomes and egret or a dog to satisfy his master´s sexual mythopoeia, and in the end he reshapes the Sorcerer´s body into a woman´s by covering him with clay and sculpting breasts, hips, and pudenda.

The portrait of a political monster is a classic Latin American genre, but Valenzuela goes deeper than her predecessors. She stays close to her subject´s flesh and wired to his nerves until he has no secrets. As the Sorcerer retreats from the Other into his ultimate fantasy about parthenogenesis, Valenzuela follows. Only when the unholy birth is about to take place does she back up, like Hitchcock´s camera, to let the Sorcerer´s tumor burst atop his lonely pyramid, fulfilling the prophecy inscribed at the beginning of the novel: “A river of blood will flow.”

The Lizard´s Tail has been published first in English translation. Valenzuela lives in New York and is an associate fellow of the Institute for the Humanities; the usual gap between original publication and translation has not only been bridged but overlapped, doubtlessly because the author is closer to her translator, the famous Gregory Rabassa. In Rabassa´s version, Valenzuela comes across as a masterful and luxuriant. Her book is a tour de force; it starts in high gear and never lets up.

Still, this is the first time I´ve read Spanish American fiction in English before Spanish, and I miss the chance to handle Valenzuela´s language directly, to converse with it face to face and feel in the texture and tone and particularly in the humor- a familial connection between writer and reader. Valenzuela has said that “to write in another language is like a betrayal if you really want to be a writer.” And to read in another language if you really want to be a reader? It probably applies, because I feel terribly guilty. To Luisa Valenzuela, then, I dedicate this, my first infidelity, mi traición.